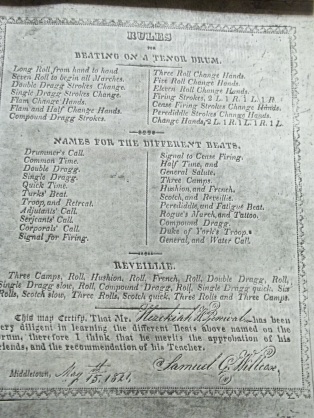

The Percival certificate, 1821. Note the second rule, which confirmed that old drummers’ joke “It starts with a seven…everything starts with a seven… Courtesy David Pear, Colchester, CT

On May 15, 1821, Hezekiah Percival of Moodus, Connecticut, was issued a certificate attesting to his proficiency on “the different Beats above named on the drum.” On it, his teacher, Samuel G. Willcox of Middletown’s Upper Houses [present-day Cromwell, CT], declared that the 20-year-old Percival “has been very diligent” and thereby “merits the approbation of his friends, and the recommendation of his Teacher.” Willcox had purchased the certificate from a local printer — a more or less generic form with blank spaces that allowed him to personalize it with date, name, and signature. Despite its fairly commonplace nature and easy availability, only one other such certificate has been discovered. It was prepared some 31 years later by another printer for another teacher who used a similar certificate and similar language to confirm the competence of his own student:

This is to certify that H.J.H. Thompson has been very diligent in attaining a knowledge of the above Rules and Beats, for which he merits the approbation of his friends and the public, and the recommendations of his teacher.

Courtesy the Connecticut Historical Society, https://chs.org/

The certificates are quite similar, even though one is dated 1821 and the other 1852. Both were professionally and attractively printed, the latter by Patten’s Job Press in New Haven, CT. They clearly outline a basic and rather traditional repertory that any 19th-century student of military drumming would be expected to master; many of the rules and beats listed thereon are included in the teaching repertory of Massachusetts drummer Benjamin Clark (1797) and are found in a variety of early-to-mid 19th-century American drum instruction publications.

The rules (rudiments) are listed on both certificates in much the same order: Long Roll, Seven Roll, Double Dragg, Single Dragg, Flam, and Flam and a Half. Also included are the Compound dragg, Firing Strokes, Cease Firing Strokes, and Perediddle Strokes as well as the three, five, and eleven-stroke rolls. However, in 1852, Thompson was taught five rudimental combinations that Percival was not: the perididdle drag, 7 roll and 4 singles, 7 roll and 6 singles, the 3 roll and compound drag, and the 3 with 6 singles. He was also expected to master the Paying [poing] Stroke. These additional rudiments were not unknown in the 1820s; indeed, the poing stroke has a long albeit unclear history that was clarified and taught in the American repertory at least by 1810. Therefore, it is difficult to ascertain why they are missing from the 1821 certificate. It is entirely possible that the combination rudiments could represent developments that occurred in military drumming over time, but another likely hypothesis is that Percival, learning to drum in a small Connecticut village, did not need to master everything expected from a city drummer like Thompson. It might also be speculated that he already knew them or learned them by necessity later on in his career. This latter interpretation becomes more viable when perusing the list of Beats, three of which (British Grenadiers, Hail Columbia, and American Eagle) appear on the Thompson certificate but not on Percival’s, even though two of them are readily found in the 1820 military march repertory and one of them, British Grenadiers, has long been a continuous staple in the core Ancient repertory in general and in the Moodus Drum and Fife Corps specifically.

The lists of rules on each certificate would be unremarkable were it not for the annotation Willcox inserted regarding their performance. He labeled every rule (except the Compound Dragg Strokes) with either “hand to hand,” “change,” or “change hands,” emphasizing the importance of playing the rudiments “hand to hand.” That is, the drummer should begin the first rudiment with the right hand but should start the second with the left, the third with the right, and so on. Thus, in executing the string of rudiments that comprise a beat, the drummer will play hand-to-hand, starting with the right hand and alternating with the left as the beat continues (except, according to Willcox, when playing the compound dragg and, in practice, when performing the single stroke roll). This is the basic tenet of rudimental drumming, so important that Willcox dared not leave it out of his written instructions but so common that Beach did not bother to write it into his.

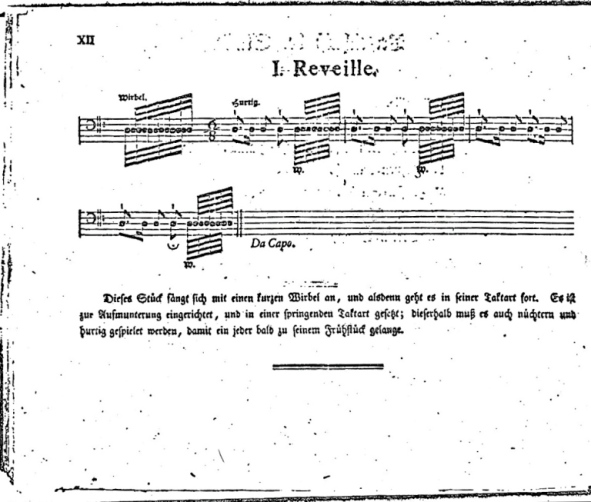

Percussionist Robin Engleman writes that this is the earliest known drumming for the Reveille [Three Camps]. George Winters, 1777, Courtesy Robin Engleman, https://robinengelman.com/category/articles/fifes-drums/page/2

Both Percival and Thompson were taught to beat Reveille in the sequence prescribed by their teachers:

-

Percival, 1821 Thompson, 1852 Three camps Three Camps roll Hussion Hessian roll French French roll Double Dragg Compound drag roll Single Dragg quick 6 rolls Scotch slow Scotch Three rolls Scotch quick Three rolls Three Camps Revelly [Three Camps]

Of note are the rolls that define the divisions in Percival’s Reveille, which are lacking in the 1852 certificate. Percival’s reveille also features a Single Dragg played quick as well as two versions of the Scotch. Even though both drummers learned their craft in Connecticut, these differences likely represent regional rather than chronological variations, especially when one realizes that it is the Percival version of the reveille, not Thompson’s, that more closely resembles what was in the mid-19th century air. (As an aside, the reveille was not standardized until 1869, when Strube’s Drum and Fife Instructor was officially recognized by the United States Army; even so, regional differences persisted beyond that date.)

Reenactors at Genessee Country Village (2006) dressed in uniforms of the NY State Militia, c, 1812. Their “tall hats” are called shakos. Courtesy of the Village, http://www.1812marines.org/news-and-events/photos/2006-events/grand-tactical-2006-genessee-village-ny/

The 1820s-30’s did not offer much occasion for Percival to practice his craft. The federal army remained small following the War of 1812; however, enrollment in Connecticut’s militia companies was strong, thriving, and required. Training days, mandated by Connecticut law, were welcomed venues for the military drummer (and fifer) to demonstrate their skills:

In 1816, there was a general re-organization of the militia throughout the State, which was preserved till within a few years [of 1884]. It is within the memory of our young men that “Training Days” were great events in the history of the town, from which all other events were dated. Soldiers with their tall hats and taller plumes, dressed in showy uniforms, met in companies in the different societies in town, once a year, where they were drilled in the manual of arms-marched in sections, platoons, and by company, and dismissed after several general discharges of musketry. How the boys reverenced these famous soldiers! The greatest scalawag in town, upon these occasions, was transformed into a hero, in their eyes, as long as he wore the regimentals.

Indeed, it was in the militia that Percival’s teacher, Samuel Willcox, found opportunity to drum. He was so good at it that he was elected drum major in 1819, two years before he taught young Hezekiah.

I have yet to find Hezekiah Percival’s name listed as a member of the local militia; however, it would be an interesting but immaterial fact if it was. Regardless of where Percival practiced his craft, his unique and lasting contribution was made in what is known as “Ancient” (rudimental), not military drumming. That occurred in 1860, when he co-founded the Moodus Drum and Fife Corps. This was – and remains — significant in many ways. Moodus is not the earliest drum corps – there are several other candidates for that, most notably the long-defunct West Granby Fife and Drum Corps. However, it is the earliest drum corps to survive continuously (it is still active today) and, more importantly, it is the earliest drum corps to survive with its primary written documentation. Furthermore, its members retain a respect for the founders bordering on reverence; therefore, very little has changed over the years in the Moodus style of tempo, performance, dress, and drill. In fact, Moodus drumming is easily traced in a continuous line from the 1821 certificate right up until today, 2018.

Studio shot of the early Moodus Drum and Fife Corps sometime after acquiring their first uniforms. According to one old-timer, they marched in street clothes until they could afford to purchase uniforms. Original unlocated, copy from Author’s Collection.

The Moodus corps is in truth a sort of musical invention. The Percivals – and maybe the West Granby men – were among the very few who could envision music of the fife and drum outside their historically traditional military confines. The sheer volume of the drums coupled with the shrill, unrefined pitch of the even-hole, straight-bore fifes precluded their use as parlor instruments, but these same features made them perfect for transmitting military commands over the din of large groups of men, ordering their marching, and regulating the functions of the military camp. In fact, the general 19th century public did not regard either the fife or the snare drum as true musical instruments at all; to them, they were simply military signal instruments that belonged outdoors. And outdoors is exactly where the Moodus corps originated in 1860, at a picnic attended by Percival, his brother Orville, and a few family members and friends. However, it wasn’t until 1861, when these same participants began to gather on occasion at the local train station to provide a patriotic musical send-off to Civil War enlistees, that the concept of a marching band comprised solely of civilian fifers and drummers, unsupported by and disconnected from the military, jelled into reality. It took only a few years for the corps to become the pride of Moodus, as this confused but essentially correct memoir relates:

The band was organized in the autumn of 1864, under the tuition of the veteran drummer [Hezekiah] W. Percival. . .many changes have occurred during the 20 years existence of the corps, yet a goodly number of of the original members remain, and the leader, Mr. PERCIVAL, though he has long since laid aside the drum and sticks, finds pleasure, in his 85th summer, in listening to the practice of his boy[s].

The author of these words, who included them in a town history published in 1884, went on to say:

The style of their playing is that of the days when their teacher was in his prime, and their costume is of the old continental fashion. Their drums, too, are of the old style, and several are now more than 100 years old yet in a perfect state of preservation.

While not a perfectly accurate memory (the corps was founded before 1864, and the “several drums” would not approach 100 years of age until about 1920-25), the author did aptly describe what the Moodus corps so admirably did and continues to do today.

Percival died in 1888 but his legacy, embodied in the certificate of merit he earned in 1821, lives on not only in the Moodus Drum and Fife Corps, but also in the many other Ancient corps it inspired. His certificate of merit remains in private hands.

The course followed by Henry James H. Thompson differs markedly from Percival’s. He, too, was 20 years old when he successfully completed his course of drum instruction, but this was during the tumultuous antebellum years that would soon culminate in the War Between the States. While Percival and his musical companions were busy inventing the Moodus Drum and Fife Corps, Thompson was serving in the fife and drum corps of the 15th Regiment of Connecticut Volunteers. The letters he wrote to his wife, Lucretia, have been preserved along with many of her replies; while these don’t reveal much about Henry Thompson the drummer, they do teach us a lot about Henry Thompson the man.

A thief in the 55th Masschusetts is paraded out of camp in 1863 to the tune of The Rogue’s March. Image Courtesy of the Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/cwp2003001683/PP/

The letters are chatty and loving, albeit not necessarily grammatical. Thompson describes the weather, the countryside, and camp life to Lucretia; at one point she learns about the discovery and punishment of a camp thief, the musical ceremony for which her husband was well prepared. He writes of his hopes (although a strong “McClellan man,” he hoped that the election of 1864 would bring peace), and he writes of his disdain for the south (New Bern was a diseased city full of loose women), but mostly he writes of his worries, especially about the progression of the war. He was one of many who believed, in the words of historian Randall C. Jimerson, that the Civil War was a “white man’s war” fought to preserve the Union; to Thompson, slavery was an increasingly bothersome nonissue.

Thompson took a dim view of the African American soldier and worried about recruiting them for the war effort. He was certain that they would be undependable in the field, and in May 1863 he told his wife, “they are all for getting out of the way when there is a battle afoot.” His negative suppositions turned into anger as the war dragged on into the summer of 1864, when his view of slaves and slavery worsened. Every freed slave, he complained, has “cost 4 thousand dollars & 1 white mans life thus far.” He fumed that, at that rate, “we shall loose 1 million of lives” and “4 million of dollars” to free a thousand slaves and concluded his rant with a dismal estimation of “3 million [slaves] yet to free.”

His opinion of white southerners was hardly better. Jimerson notes an incident that occurred in October 1862:

After returning from a raid into eastern North Carolina, [Thompson] reported that the inhabitants ‘dont know that there side have ever fired on Fort Sumpter we asked them if they didnt read it in the papers they said they never had any. they eat with their hands they have no knives & forks.’

He continued, “I dont know what you think about such an ignorant class of people in the United States but I know what I think And I am surprised & astonished!” He further assured a possibly incredulous Lucretia that “all I have wrote is true.”

Group of freed slaves in Richmond, VA. Copied from an 1865 stereocard. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/cwp2003005762/PP/

The brutality of the war, though, was what shocked Thompson the most. This is what echoes throughout the letters they wrote and saved. Early in his enlistment he confided that, “I have seen horible sights men with their heads blowed off and legs and armes and shot through the body.” It’s little wonder that he wrote even more somber thoughts to Lucretia only two days later, “We are all tired of the war the whole army we never shall whip them.” To him, the war was nothing but “a great slaughter of lives.”

Lucretia agreed. She missed her husband terribly and several of her letters urge him to “take a long step” and “return home to comfort and protect his family.” Jimerson, though, discovered that Lucretia lured her husband with more than just her desire for protection and comfort:

In closing one letter, Lucretia added. “3000 kisses PS if you was at home the[re] would [be] something done besides sending kisses.” Henry felt the same. “I shant tell you what I dreamed last night olney I was 2 home and we was 2 bed.”

They would have to wait until the summer of 1865 for Henry to complete his three-year enlistment and lawfully head home. The reunited family lived unpretentiously in the New Haven area for many years. In 1885 Thompson was awarded a pension for his wartime services, and by 1900 his name appears on the roster of the Admiral Foote Post No. 17 in New Haven, Department of Connecticut, G.A.R. But not for long. Thompson died in 1901 at the age of 69. His certificate is preserved in the archives of the Connecticut Historical Society in Hartford.

Copyright January 2018, History of the Ancients Dot Org. All rights reserved.

![The East Hampton Ancients, [ca. 1922?] Author's Collection.](https://historyoftheancients.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/craigs-list-bed.jpg?w=300&h=224)

![Camp Grant, Portland [ME] G.A.R. Convention, 1885. Accessed from https://www.mainememory.net/sitebuilder/site/1937/page/3186/display?use_mmn=1](https://historyoftheancients.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/portland-maine-1885-gar.jpg?w=630)